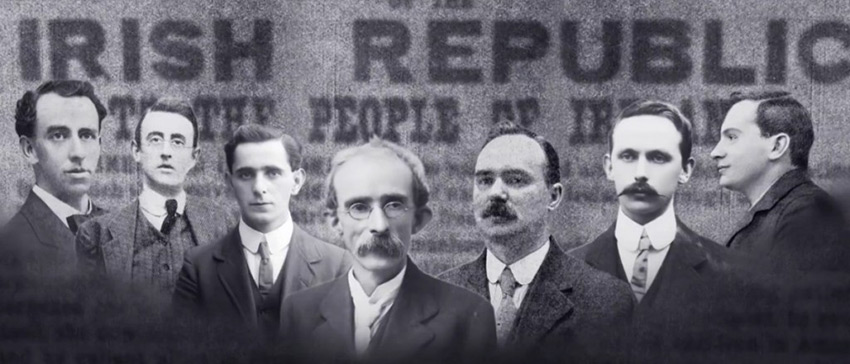

Students of Irish History know the name Daly. Edward (Ned) Daly was the youngest of the 1916 leaders executed by the English in May 1916 and Kathleen Daly Clarke was Ned’s sister and wife of chief architect of the rising, Tom Clarke. Clarke was the first of the 1916 leaders to face the firing squad in Kilmainham Jail. Kathleen herself was fully involved in the rising and was imprisoned for republican activity in 1918. She remained active in Irish public service and served in the Dail, the Senate, and as Mayor of Dublin through the early decades of the Irish Free State.

What may not be as well known is that the Daly family of Limerick has a nationalist lineage that harkens back to the United Irishmen of 1798 and one that reaches forward to Albany, NY in 2017.

Angela Doyle McNerney was born in Albany in 1961 and is the great grandniece of Ned Daly and Kathleen Daly Clarke. Her connection is through her mother Terry O’Toole Doyle who was born in Ireland in 1937, and Angela says she doesn’t remember a time when she wasn’t aware that she was related to people who changed Irish history. Her mother did not overplay the Daly history, but she made Angela aware that her forbearers, especially the women, were strong and independent, fought for their country, and carried arms alongside the men. Angela said, “My parents were poster children for the differences between the Irish and Irish Americans. My Irish born mother was quiet about our family history, and for my 2nd generation Irish American father, the Dalys were bragging rights at the AOH hall.”

Angela Doyle McNerney was born in Albany in 1961 and is the great grandniece of Ned Daly and Kathleen Daly Clarke. Her connection is through her mother Terry O’Toole Doyle who was born in Ireland in 1937, and Angela says she doesn’t remember a time when she wasn’t aware that she was related to people who changed Irish history. Her mother did not overplay the Daly history, but she made Angela aware that her forbearers, especially the women, were strong and independent, fought for their country, and carried arms alongside the men. Angela said, “My parents were poster children for the differences between the Irish and Irish Americans. My Irish born mother was quiet about our family history, and for my 2nd generation Irish American father, the Dalys were bragging rights at the AOH hall.”

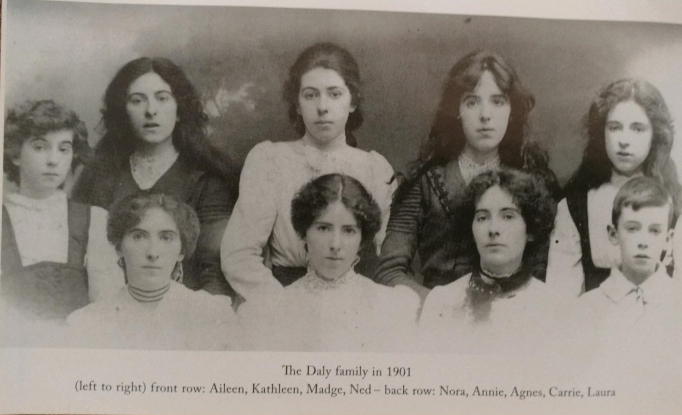

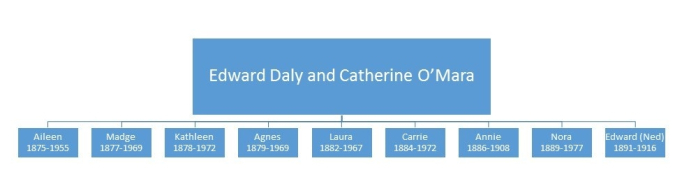

Angela’s recorded republican lineage goes back to 1798. According to cousin and author, Helen Litton, Angela’s 4th great grandfather, John Daly, was a scribe from Galway and took part in the rebellion of the United Irishman. His son and Angela’s 3rd great grandfather, another John Daly, appears in the census in the city of Limerick a couple of decades later, and was active in Dan O’Connell’s repeal-of-the-union movement. And his two sons, Edward (Angela’s 2nd great grandfather) and John, were renowned Limerick Fenians, taking part in the Rising of 1864. Both brothers were imprisoned for their participation. John was imprisoned a second time for 12 years, and suffered solitary confinement, hard manual labor, and constant hunger. His health was compromised for the rest of his life. John emerged as the Godfather of the Fenians at the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century establishing both Limerick as a vital nationalist city and the Daly family as the first family of Republicanism. One historian calls the Dalys, Fenian royalty. John never married, but he assumed the patriarchal role of Edward’s family in 1900. Edward married Catherine O’Mara and had nine children in twelve years – eight daughters and one son. Edward died while Catherine was pregnant with the ninth child. That child was another Edward (Ned) Daly, the 1916 hero. The eldest of the nine children was Aileen Daly, Angela Doyle McNerney’s great grandmother.

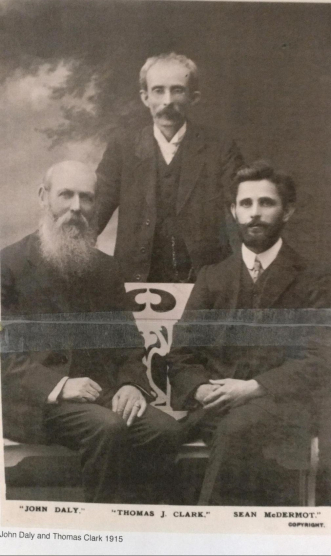

When Fenian John Daly assumed responsibility of Edward’s family, he opened up a bakery on William St. in Limerick, a bakery that the nieces and nephew worked in at one time or another, and a place that became the republican nerve center in the city. The bakery was the first in Limerick to have the family name in Irish above the door and on the delivery wagons. John also had enormous political influence on his nieces and nephew. Already aware of their nationalist heritage and sympathetic to Irish republicanism, Uncle John’s presence committed the family to 1916, and made the bakery and the family home centers of revolutionary activity. Every important 20th century leader made the pilgrimage to John in Limerick and were in and out of the Daly home: Padriag Pearse, Sean MacDiarmada, Roger Casement, Sean Heuston, Con Colbert, and Tom Clarke, to name a few. Bakery funds financed the two Limerick battalions of Irish Volunteers, supported the IRB newspaper, and provided land for and built the Fianna Hall behind their Barrington St. home. They kept the IRB afloat after the American Clan na Gael ran out of money. Many historians claim the IRB would not have lasted until 1916 without the Daly family. By April 1916, John was bound to a wheel chair and very frustrated that he could not be in Dublin. He died a month after the 16 organizers of the Easter Rising were executed — first among them, his nephew, Ned, and dear friends, Tom Clarke and Sean MacDiarmada. Angela’s cousin, Derville Potter, said the family was utterly devastated by 1916.

This was the atmosphere Albany’s Angela Doyle McNerney’s great grandmother, Aileen, grew up in, and a legacy that has been handed down through the generations to Angela and her brother, Tom.

It was Aileen’s sisters, Madge, who grew to be a nationalist force to be reckoned with in Limerick, and Kathleen who had a similar role in Dublin. Madge formed and led the Limerick branch of Cumann na mBan (the Women’s League, created as an auxiliary to the men’s Irish Volunteers), in 1914. The Limerick branch was very active in raising money, in distributing flyers, in hosting lectures, and in arms training. Madge managed the bakery for her uncle and used it as a communications center for the Irish Volunteers and the secret IRB up to 1916 and then for the IRA in the War of Independence. Family stories talk of messages being baked into bread or stuffed into bags of flour and the frightening raids of the Black and Tans. Eamon DeValera was in the house during one raid. Madge and her sisters successfully hid him between the mattress and box spring of their mother’s bed while their mother was in it. Dev said he nearly suffocated. Madge’s Witness Statement is available on the website of the Irish Bureau of Military History.

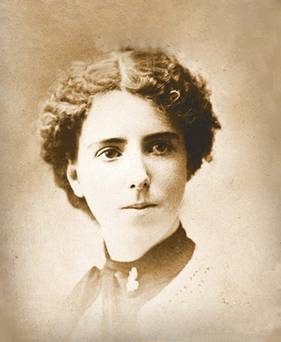

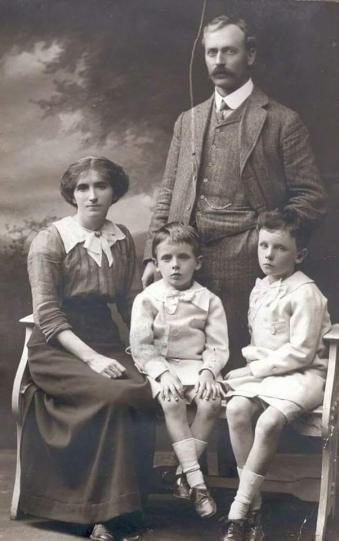

Kathleen married Tom Clarke, 20 years her senior and an old Fenian friend of John Daly. The men had met in prison. Clarke, too, was a member of the IRB. After a few years in America, Tom and Kathleen returned to Dublin in 1907 to be in the center of the planning of the Rising. They opened a tobacco shop on the north side of the city which became a front for their revolutionary activities. Kathleen was a full partner to Tom in writing articles, in passing messages, and in raising money. Like Madge in Limerick, Kathleen was a founding member of a branch of Cumann na mBan: the main branch in Dublin. After Tom’s execution, Kathleen coordinated the distribution of aid to the families of those killed or imprisoned, and kept the republican network alive. Kathleen was active during the War of Independence raising money and offering her home as a safe house and was imprisoned for 8 months in 1918 with Constance Markievicz for her involvement. She later worked as a Justice in the Sinn Fein courts in Dublin, was an active member of the White Cross, and, while opposing the treaty, worked on a committee to reconcile the pro- and anti-treaty factions. Kathleen’s continued activism for Ireland is immense: She was a founding member of Fianna Fail, served in the Senate, and was the first woman Lord Mayor of Dublin from 1939-1943. In 1965, she left Ireland to live near her youngest son in Liverpool, but returned to participate in the 1966 commemoration of 1916. During the ceremony, she announced publically for the first time that her husband Tom Clarke was the true first president of the Irish Republic and that Padraig Pearse claimed the spotlight. She was given a full state funeral when she died in 1972.

Kathleen married Tom Clarke, 20 years her senior and an old Fenian friend of John Daly. The men had met in prison. Clarke, too, was a member of the IRB. After a few years in America, Tom and Kathleen returned to Dublin in 1907 to be in the center of the planning of the Rising. They opened a tobacco shop on the north side of the city which became a front for their revolutionary activities. Kathleen was a full partner to Tom in writing articles, in passing messages, and in raising money. Like Madge in Limerick, Kathleen was a founding member of a branch of Cumann na mBan: the main branch in Dublin. After Tom’s execution, Kathleen coordinated the distribution of aid to the families of those killed or imprisoned, and kept the republican network alive. Kathleen was active during the War of Independence raising money and offering her home as a safe house and was imprisoned for 8 months in 1918 with Constance Markievicz for her involvement. She later worked as a Justice in the Sinn Fein courts in Dublin, was an active member of the White Cross, and, while opposing the treaty, worked on a committee to reconcile the pro- and anti-treaty factions. Kathleen’s continued activism for Ireland is immense: She was a founding member of Fianna Fail, served in the Senate, and was the first woman Lord Mayor of Dublin from 1939-1943. In 1965, she left Ireland to live near her youngest son in Liverpool, but returned to participate in the 1966 commemoration of 1916. During the ceremony, she announced publically for the first time that her husband Tom Clarke was the true first president of the Irish Republic and that Padraig Pearse claimed the spotlight. She was given a full state funeral when she died in 1972.

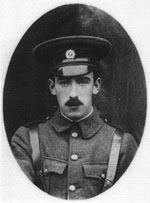

John Daly worried that his brother’s youngest child, Ned, was not focused enough on a career or the republican cause, and that he’d been too “mollycoddled” by his mother and eight sisters. Ned bounced from job to job and focused more on amateur musicals than politics. After an explosive argument in 1910, John evicted Ned from the family home. Ned moved in with Kathleen, Tom, and their three sons in Dublin, and perhaps their influence ignited his commitment to republicanism. In 1911, he joined the Irish Volunteers and soon after was sworn into the IRB. He grew into a disciplined volunteer and rose to the rank of commander. On Easter Monday 1916, he commanded the unit at the Four Courts, and earned great loyalty and respect from his troops. He was executed the day after Tom Clarke, and the story passed down in the Daly family says his parting words to his three sisters who sat with him in his cell were, “tell Uncle John I did my best.”

John Daly worried that his brother’s youngest child, Ned, was not focused enough on a career or the republican cause, and that he’d been too “mollycoddled” by his mother and eight sisters. Ned bounced from job to job and focused more on amateur musicals than politics. After an explosive argument in 1910, John evicted Ned from the family home. Ned moved in with Kathleen, Tom, and their three sons in Dublin, and perhaps their influence ignited his commitment to republicanism. In 1911, he joined the Irish Volunteers and soon after was sworn into the IRB. He grew into a disciplined volunteer and rose to the rank of commander. On Easter Monday 1916, he commanded the unit at the Four Courts, and earned great loyalty and respect from his troops. He was executed the day after Tom Clarke, and the story passed down in the Daly family says his parting words to his three sisters who sat with him in his cell were, “tell Uncle John I did my best.”

The rest of the Daly siblings were involved in the nationalist movement to varying degrees. Laura and Nora carried messages baked into loaves of bread or stuffed into sacks of flour to designated meeting places. Sometimes the two sisters transported the flour sacks on the train from Limerick to their sister Kathleen or another republican bakery in Dublin. One story tells of Laura and Nora in the Dublin bakery with a young Michael Collins. Apparently the warning was sounded that the Tans were coming down the road and would soon be at the bakery. Collins ran flour through his dark hair, put on an apron, and stood behind the counter. The story goes that he actually sold bread to a couple of Black and Tan soldiers who came into the bakery looking for him. The Tans slashed bags of flour missing the notes and missing the collection of firearms stored in a broken oven, and of course missing Collins. Laura and Nora even came to Dublin before Easter to help in the rising and were given instructions on Easter Monday to travel immediately by train to Cork to attempt to deliver the message to the Volunteers in Cork City that the rising was on. British troops had secured the city at that point, however, so the sisters never made it to the IRB command. Both married men active in the movement: Laura married Jim O’Sullivan, a close friend of her brother Ned, who was with Ned at the Four Courts during Easter week 1916, and who was imprisoned in Britain after the rising for 5 years. Nora married Eamonn Dore, Sean MacDiarmada’s body guard. Both couples settled in Limerick after the treaty and helped run the bakery. The Dalys were vehemently anti-treaty, while O’Sullivan and Dore, while not loudly defending the treaty, were devoted to Michael Collins. Collins was Godfather to one of Jim and Laura O’Sullivan’s children.

Agnes, Carrie, and Annie Daly of course grew up in the Republican household, worked in the bakery, and listened to their Uncle John’s opinions. They were not, however, politically active. Annie died young at 21 of typhus, and Carrie and Agnes were not active participants nor did they ever marry. It is a sad irony that of all the Daly siblings, it was Agnes who was brutally pulled out of the family home by the Black and Tans during the War of Independence during one of their many raids on the Daly home. Dragged by the hair, her head was shaved and her thumb was nearly severed from her hand by a knife.

Angela’s great grandmother, Aileen was the eldest and married Ned O’Toole, Limerick City Treasurer, in 1905. She was a young mother in 1916, so she was not actively involved in the rising, but her husband, Ned O’Toole, was a commander in the Limerick Irish Volunteers. On Easter Monday 1916, he obeyed Eoin MacNeill’s countermand to stand down. Even though no one outside of Dublin participated in the rising, the inaction of Limerick’s volunteers caused deep discord in the Daly family. Uncle John and Madge were furious that Limerick did not rise anyway.

Angela’s great grandmother, Aileen was the eldest and married Ned O’Toole, Limerick City Treasurer, in 1905. She was a young mother in 1916, so she was not actively involved in the rising, but her husband, Ned O’Toole, was a commander in the Limerick Irish Volunteers. On Easter Monday 1916, he obeyed Eoin MacNeill’s countermand to stand down. Even though no one outside of Dublin participated in the rising, the inaction of Limerick’s volunteers caused deep discord in the Daly family. Uncle John and Madge were furious that Limerick did not rise anyway.

Ned O’Toole, remained active during the early part of the War of Independence – his young son, John, Angela’s grandfather, carried rebel messages around town at 8 years of age. Such was the family split, however, that Aileen and Ned O’Toole left Ireland for the US with their two sons in 1920. They were in the US long enough for the two sons to become American citizens. The family returned to Limerick during the Depression years later, and Ned found work with Madge who by that time had become a wealthy property owner. Ned and Aileen’s son, John (Angela’s grandfather), in turn left Ireland with his wife and three children in the 1940s for America ostensibly because John was called to serve in the US military during WW2, but Angela’s Uncle Brian O’Toole suspects his father never adjusted to the rigid Irish society, and Angela, herself, suspects her grandfather did not want to feel obligated to the Dalys and wanted to escape the political and family “darkness.” John and his family settled in White Plains. One of his children, Terry, is Angela’s mother.

Terry and her sister, Eileen, and brother, Brian were sent back to boarding school in Dublin in 1943. Madge was then living in Dublin with her two sisters Agnes and Carrie. The three children spent occasional weekends with the great aunts, and Terry appreciates the responsibility the aging aunts assumed for three preteen children.

The aunts, however, rarely talked much about the republican heritage of the Daly family. Terry does have one memory that in retrospect reveals the patriotic passion of her aunts. On their seaplane flight from New York to Dublin, the children had a layover in London where eight-year-old Terry bought a postcard of Princess Elizabeth. In Dublin, the children were brought to their aunts’ home. When Terry showed Madge the postcard, Madge took it from her, tore it up, and walked out of the room. Another story, remembered by Terry’s brother Brian, involved Madge taking a revolver out of a drawer wrapped in a towel. She told him Eamon DeValera stopped in their house in Limerick while on the run during the War of Independence and asked her to hide his revolver. He never returned for it and Madge held on to it for the rest of her life.

Terry and her siblings returned to the US in early adolescence. Terry earned a BS in education from SUNY Plattsburgh and, while student teaching in Ballston Spa, met John Doyle, who had just returned from Korea. They married in 1959 and moved to Albany. Terry maintains contact with her cousins in Ireland and has created her own archives of the family history. Angela grew up on the stories of revolutionaries and has proudly passed them along to her sons, Shane, Dylan, and Rory. Dylan once said, “I like the fact that our relatives are part of the history of Ireland.”