Helen O’Hanlon Carswell was born in 1936 on a farm in Schodack Landing to Michael “Mick” O’Hanlon and Ellen O’Connell. Both of her parents were born in Burnfort, County Cork, a small crossroad just south of Mallow. Mick, born in 1887, and Ellen, born in 1895, were married in Burnfort in 1920, but emigrated separately. Mick came in 1921 leaving Ellen and two children in Burnfort with Ellen’s mother. Ellen and the children followed in 1927. Mick initially joined his brother in Westchester County where they worked as gardeners for wealthy estate owners. By 1927, he saved up enough money to buy a farm in Schoharie County and bring Ellen and the children over. Once reunited in America, the O’Hanlon’s had five more children. Helen is the youngest. From Schoharie, the family moved to another farm in Schodack Landing. In the early 1940s, Mick found a job on the railroad and the family moved to Livingston Ave. in St. Joseph’s parish in Albany.

Helen O’Hanlon Carswell was born in 1936 on a farm in Schodack Landing to Michael “Mick” O’Hanlon and Ellen O’Connell. Both of her parents were born in Burnfort, County Cork, a small crossroad just south of Mallow. Mick, born in 1887, and Ellen, born in 1895, were married in Burnfort in 1920, but emigrated separately. Mick came in 1921 leaving Ellen and two children in Burnfort with Ellen’s mother. Ellen and the children followed in 1927. Mick initially joined his brother in Westchester County where they worked as gardeners for wealthy estate owners. By 1927, he saved up enough money to buy a farm in Schoharie County and bring Ellen and the children over. Once reunited in America, the O’Hanlon’s had five more children. Helen is the youngest. From Schoharie, the family moved to another farm in Schodack Landing. In the early 1940s, Mick found a job on the railroad and the family moved to Livingston Ave. in St. Joseph’s parish in Albany.

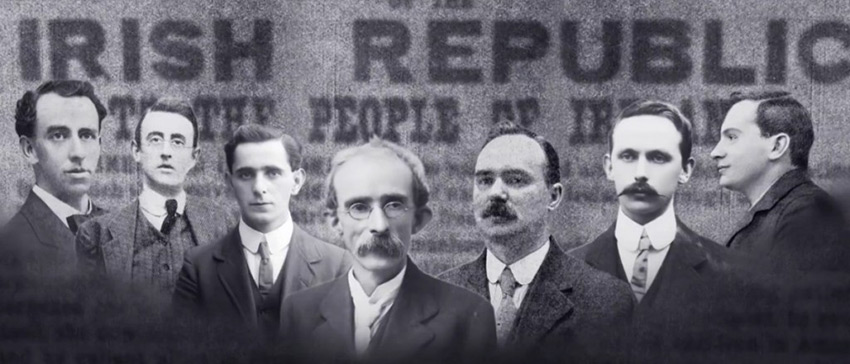

Helen suspects her father had to flee Ireland in 1921. Mick joined the Burnfort Brigade of the Irish Volunteers before the Easter Rising, practicing with broom sticks in the evening and on weekends, and was active in the IRA after the rising. Names that are well known to Irish historians, such as Tomas Mac Curtain, Terence MacSwiney, and Ernie O’Mally are part of Mick O’Hanlon’s story. Helen has speculated about her father’s activities over the years. The shooting of Tomas Mac Curtain in March 1920, the burning of Cork City in December the same year, and Mick’s hasty departure from Ireland with falsified papers in early 1921 are most likely connected.

Mick probably joined the Irish Volunteers as soon as the group was formed in 1913. He was involved in a plan to pick up German arms along the Cork coast in early 1916, a plan that was thwarted by the group taking the wrong fork on a dark moonless night as they made their way to the coast. The wrong turn was actually life-saving because an informer had told the authorities about the arms delivery, and British soldiers were waiting at the coastal pick-up point. Just after the Easter Rising, the force of not only the British authorities, but also the Catholic Church and local elders, compelled the people of Burnfort and the surrounding townlands to turn in their arms to the church to avoid their homes and farms from being ransacked by the British. Some did and some didn’t, but there was a decent cashe of weapons turned in. Mick and one other man broke into the church during the night, took the weapons, greased and wrapped them, and buried them. No one knew Mick had been involved in the operation until the 1960s, 45 years later.

Between 1947 and 1957, the Irish government began collecting oral histories of the revolutionary years from 1913-1921 by those directly involved. The oral histories were transcribed in the 1950s and digitized five years ago. They are now available and searchable on the website of The Bureau of Military History (http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/) Of the 1,773 witness statements collected, two accounts, one by John O’Sullivan and the other by Cornelius O’Regan, both from the Mallow area, state that Mick Hanlon was an officer in the Mourneabbey Company, a larger body that included the Burnfort Brigade.

O’Sullivan said: “There was not activity in the area until late in 1917 when the Irish Volunteers were reorganized. On the reorganization there were a number of new recruits … These men, with one or two others, formed a new section of Mourneabbey Company in Beanaskeha area. I was section leader. The usual training in close order drill was carried out in the fields in the area – usually at night. The strength of Mourneabbey Company was now about 60. The company officers, who were elected, were: O/C Bill Jones; 1st Lieut., Mick Hanlon; 2nd Lieut., Paddy McCarthy.”

A classmate of Mick’s at the Burnfort school was Tomas Mac Curtain. Mac Curtain was one of the founding members of the Irish Volunteers and commanded over 1000 volunteers in April 1916. In anticipation of the Rising, he had volunteers positioned in various locations around County Cork awaiting the command to revolt, but with the confusion of Owen MacNeill’s countermand, word never came, and the Cork forces never rose. Tom Clarke sent his sisters-in-Law, Laura and Nora Daly, to Cork to give the order in person, but by the time they arrived, British troops had surrounded the city and confiscated Volunteer arms. Mac Curtain was imprisoned in the famous Frongoch Prisoner of War camp in Wales along with scores of men involved in the Dublin rising, and when he returned to Cork 18 monthes later, he resumed active duty as a Commandant of what was now the Irish Republican Army. By 1918, Mac Curtain was a brigade commander – the highest and most important rank in the IRA, and was elected Sinn Fein Lord Mayor of Cork in January 1920.

A classmate of Mick’s at the Burnfort school was Tomas Mac Curtain. Mac Curtain was one of the founding members of the Irish Volunteers and commanded over 1000 volunteers in April 1916. In anticipation of the Rising, he had volunteers positioned in various locations around County Cork awaiting the command to revolt, but with the confusion of Owen MacNeill’s countermand, word never came, and the Cork forces never rose. Tom Clarke sent his sisters-in-Law, Laura and Nora Daly, to Cork to give the order in person, but by the time they arrived, British troops had surrounded the city and confiscated Volunteer arms. Mac Curtain was imprisoned in the famous Frongoch Prisoner of War camp in Wales along with scores of men involved in the Dublin rising, and when he returned to Cork 18 monthes later, he resumed active duty as a Commandant of what was now the Irish Republican Army. By 1918, Mac Curtain was a brigade commander – the highest and most important rank in the IRA, and was elected Sinn Fein Lord Mayor of Cork in January 1920.

In mid-1918, Mick O’Hanlon left Burnfort for Cork city where he ran a pub. The city was second only to Dublin in IRA activity, and Helen speculates that he was working closely with Mac Curtain on IRA activities in Cork city, and was scheduled to be at Mac Curtain’s home “for a card game” on March 20, 1920, the night the RIC broke into the Mac Curtain home and shot the 36 year old Tomas in front of his wife and children. Helen said she never knew her father to play cards and wonders if her father too would have been killed that night. Helen guesses that her father continued IRA work with Mac Curtain’s successor, Terence MacSwiney (who was himself arrested in August 1920 and died on a hunger strike in October), and may have been involved in the IRA ambush of a British Auxiliary patrol in November that resulted in the death of one of the auxiliaries. Mick was also in Cork on December 11 and 12, 1920, the night Black and Tans set fire to Cork city in retaliation. Homes were burned, shops looted, civilians beaten, and firemen’s hoses cut. Shortly after the Cork fire, Mick left Ireland. Helen wonders if he was advised to get out by his IRA commander. Perhaps, like Mac Curtain and MacSwiney, he was targeted by the British. Well into his 30s at the time he left, Mick added two years to his passport, perhaps, again this is Helen’s speculation, to appear to the authorities to be a different Michael O’Hanlon

Helen’s mother’s side of the family also supported Irish freedom, albeit in a more circumspect way. Ellen O’Connell’s father was the post master in Burnfort, a very important job, for the Post Office was not only the center of incoming and outgoing communication in an era without phone, it was also a small shop, a bank, and a gathering place for the town. Ellen’s father, Geoffrey O’Connell, died when Ellen was only 10 and her mother assumed the position of Post Mistress. Ellen and her siblings helped out in the shop. During the War of Independence, the Black and Tans raided the town often. On one occasion, the Tans were searching for a young IRA man after an ambush. Ellen’s sister Bridget, around 23 years old at the time, gave a false alibi for the fugitive swearing he had been dancing at the post office during the ambush. Helen also heard about the Black and Tans rushing into her grandmother’s home and knocking religious statues off of a tables to the horror of the family within.

Helen’s mother’s side of the family also supported Irish freedom, albeit in a more circumspect way. Ellen O’Connell’s father was the post master in Burnfort, a very important job, for the Post Office was not only the center of incoming and outgoing communication in an era without phone, it was also a small shop, a bank, and a gathering place for the town. Ellen’s father, Geoffrey O’Connell, died when Ellen was only 10 and her mother assumed the position of Post Mistress. Ellen and her siblings helped out in the shop. During the War of Independence, the Black and Tans raided the town often. On one occasion, the Tans were searching for a young IRA man after an ambush. Ellen’s sister Bridget, around 23 years old at the time, gave a false alibi for the fugitive swearing he had been dancing at the post office during the ambush. Helen also heard about the Black and Tans rushing into her grandmother’s home and knocking religious statues off of a tables to the horror of the family within.

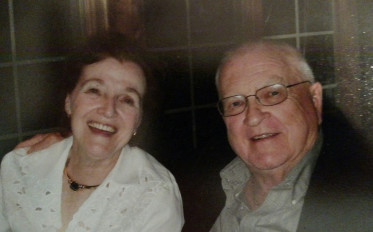

Ellen remained in Burnfort with her two children until Mick sent for them in 1927, and the family was reunited in America. Helen spent her formative years in Albany where she met and married a cousin, Eugene O’Hanlon. Eugene was also from Burnfort. Helen laughs that she didn’t have to change her name. Helen and Eugene and their five children lived in St. Teresa’s parish in Albany, were active in the AOH, and visited Burnfort occasionally through the years. Eugene died in 1992. Through her neighborhood and parish, Helen and Eugene were friends with John and Elaine Carswell. Elaine died in 1997, and a year later, Helen and John, friends for 35 years, were married. They remain very active in the AOH and CDIAA, and were honored in June 2017 as “Volunteers of the Year” for their care of the Famine Remembrance Garden in front of Hibernian Hall on Ontario Street in Albany.

Ellen remained in Burnfort with her two children until Mick sent for them in 1927, and the family was reunited in America. Helen spent her formative years in Albany where she met and married a cousin, Eugene O’Hanlon. Eugene was also from Burnfort. Helen laughs that she didn’t have to change her name. Helen and Eugene and their five children lived in St. Teresa’s parish in Albany, were active in the AOH, and visited Burnfort occasionally through the years. Eugene died in 1992. Through her neighborhood and parish, Helen and Eugene were friends with John and Elaine Carswell. Elaine died in 1997, and a year later, Helen and John, friends for 35 years, were married. They remain very active in the AOH and CDIAA, and were honored in June 2017 as “Volunteers of the Year” for their care of the Famine Remembrance Garden in front of Hibernian Hall on Ontario Street in Albany.