Mary Ellen Gallagher Lasch grew up on Harris Ave. and Ramsey Place in Albany with her brother Philip and her sisters Barbara and Theresa. Her parents, Mary Catherine Nally and Philip Gallagher, were proud of their Irish roots and fostered a sense of Irish pride in their children. Her maternal grandfather, Thomas Nally, emigrated from County Longford in 1884, and on the Gallagher side, the immigrants date back to the famine and even before, to the digging of the Erie Canal. It is through her Albany born father, Philip Gallagher, that the family has a connection to the revolutionary events of the early 20th century in Ireland.

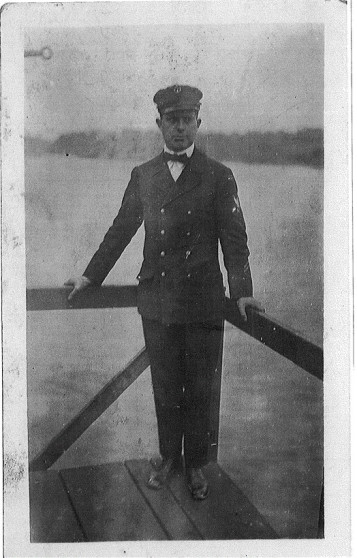

Philip enlisted in the US Navy in early 1918 when the United States entered World War I. He sailed out of New York harbor a few weeks later not knowing where he was headed. By April 10, 1918 he knew he was heading for Ireland, for he wrote his mother that he would be stationed in “the land of her mother”. A measles outbreak kept the sailors in Cork for almost a month, and in his first letters home, Gallagher wrote of the “Sinn Feiners” who were refusing to enlist in the British military and of the unrest over conscription. Buying a newspaper from an elderly women at an outside stall, Gallagher asked why the Irish would not join the fight and was told in no uncertain terms, “We’ll fight when we’ve a country to fight for.”

Philip enlisted in the US Navy in early 1918 when the United States entered World War I. He sailed out of New York harbor a few weeks later not knowing where he was headed. By April 10, 1918 he knew he was heading for Ireland, for he wrote his mother that he would be stationed in “the land of her mother”. A measles outbreak kept the sailors in Cork for almost a month, and in his first letters home, Gallagher wrote of the “Sinn Feiners” who were refusing to enlist in the British military and of the unrest over conscription. Buying a newspaper from an elderly women at an outside stall, Gallagher asked why the Irish would not join the fight and was told in no uncertain terms, “We’ll fight when we’ve a country to fight for.”

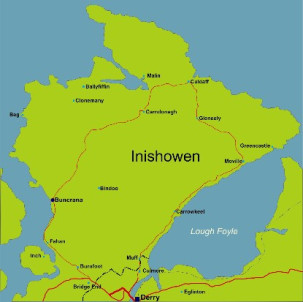

When the quarantine was lifted, Gallagher and several of his mates were sent north of Derry to be part of the construction crew building the US Lough Foyle Naval Air Station in Ture on the Inishowen Peninsula. While stationed there, Gallagher wrote 50 letters home, letters still read and reread by his children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren. He told his family that he went into the city of Derry on a regular basis and became friends with several Derry natives. One family in particular, the O’Neills, took him under their wings and invited him to dinner often at their grand Northland Road home. Gallagher wrote his mother after one dinner at the O’Neill’s, “There were three English officers and their wives there. Mr. Charles O’Neill had intended to give me a brief history of Irish politics but when the Englishmen came in he had to leave it go. Miss O’Neil told me they had to be very careful … However, she said her brother wanted me to go back with the truth, and they would arrange for a future date. Every one of them has Irish history on the tip of their fingers.” Gallagher wrote in another letter home, “I was in the [barber] shop last week when [Charles] O’Neill came in. I had quite a talk with him. After he went out, the [barber] and I were talking about him and he told me, ‘Gallagher, there’s a man with education, social standing better than anyone in the city, and worth 5 million dollars, in fact everything should warrant him mayor of this city, but they won’t give it to him because he is a Catholic, and it is written in the law no Catholic shall hold that office in Derry’ … I merely write this to show the feeling existing religiously.”

When the quarantine was lifted, Gallagher and several of his mates were sent north of Derry to be part of the construction crew building the US Lough Foyle Naval Air Station in Ture on the Inishowen Peninsula. While stationed there, Gallagher wrote 50 letters home, letters still read and reread by his children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren. He told his family that he went into the city of Derry on a regular basis and became friends with several Derry natives. One family in particular, the O’Neills, took him under their wings and invited him to dinner often at their grand Northland Road home. Gallagher wrote his mother after one dinner at the O’Neill’s, “There were three English officers and their wives there. Mr. Charles O’Neill had intended to give me a brief history of Irish politics but when the Englishmen came in he had to leave it go. Miss O’Neil told me they had to be very careful … However, she said her brother wanted me to go back with the truth, and they would arrange for a future date. Every one of them has Irish history on the tip of their fingers.” Gallagher wrote in another letter home, “I was in the [barber] shop last week when [Charles] O’Neill came in. I had quite a talk with him. After he went out, the [barber] and I were talking about him and he told me, ‘Gallagher, there’s a man with education, social standing better than anyone in the city, and worth 5 million dollars, in fact everything should warrant him mayor of this city, but they won’t give it to him because he is a Catholic, and it is written in the law no Catholic shall hold that office in Derry’ … I merely write this to show the feeling existing religiously.”

By the fall of 1918, Gallagher was attending nationalist rallies and Sinn Fein fund-raising concerts in Derry. In anticipation of the upcoming General Irish election for representatives in Parliament, he wrote to his mother, “They say that Sein Fein will win and if it is true, I shouldn’t be surprised if there was trouble. Sein Fein candidates are not allowed to sit in the House of Commons but will make their own laws in Dublin. You can see the consequence if Sein Fein is truly in.”

The election was held in December 1918, and 75 of the 105 Irish seats went to Sinn Fein. When a Derryman, Joseph O’Doherty won the Donegal seat on the Sinn Fein ticket, Gallagher was at the victory party on Creggon St. “Last night I was at the home of [Joseph] O’Doherty. He has just been selected on the Sein Fein ticket to represent the city of Derry in parliament, although he will not take his seat. There were seven priests at the gathering; one was our chaplain. The man-elect was in bed sick and when they brought me in to see him, there he lay on an old fashioned bed in a small room with only the pictures of our Blessed Mother and Lord on the walls. It reminded me of the stories of Ireland I often heard of the real leader being a humble man held in suppression by his enemies and dying heart broken. Father Hutcheson tells me he is one of the best lawyers in Ireland.”

The election was held in December 1918, and 75 of the 105 Irish seats went to Sinn Fein. When a Derryman, Joseph O’Doherty won the Donegal seat on the Sinn Fein ticket, Gallagher was at the victory party on Creggon St. “Last night I was at the home of [Joseph] O’Doherty. He has just been selected on the Sein Fein ticket to represent the city of Derry in parliament, although he will not take his seat. There were seven priests at the gathering; one was our chaplain. The man-elect was in bed sick and when they brought me in to see him, there he lay on an old fashioned bed in a small room with only the pictures of our Blessed Mother and Lord on the walls. It reminded me of the stories of Ireland I often heard of the real leader being a humble man held in suppression by his enemies and dying heart broken. Father Hutcheson tells me he is one of the best lawyers in Ireland.”

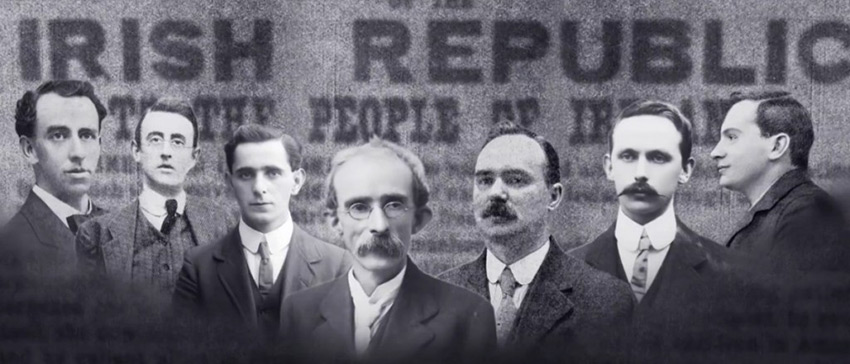

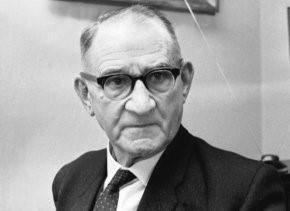

Joseph O’Doherty was indeed a lawyer and an executive member of the Irish Volunteers during the Easter Rising. He remained an executive until 1921. He was arrested after the rising and sent to prisons in County Down and Wales and was perhaps the last person to speak to Padraig Pearce – through a window, some say – before he was executed. All the Sinn Fein representatives who won in 1918 refused to take their seats in Parliament and instead assembled in Dublin on January 21, 1919 and formed their own “Dáil Éireann” or Assembly of Ireland. This first group is known today as the first Dáil, and their meeting was a declaration of Irish independence from Britain. This meeting also began the Irish War of Independence.

Joseph O’Doherty was indeed a lawyer and an executive member of the Irish Volunteers during the Easter Rising. He remained an executive until 1921. He was arrested after the rising and sent to prisons in County Down and Wales and was perhaps the last person to speak to Padraig Pearce – through a window, some say – before he was executed. All the Sinn Fein representatives who won in 1918 refused to take their seats in Parliament and instead assembled in Dublin on January 21, 1919 and formed their own “Dáil Éireann” or Assembly of Ireland. This first group is known today as the first Dáil, and their meeting was a declaration of Irish independence from Britain. This meeting also began the Irish War of Independence.

O’Doherty was re-elected at the 1921 general election and opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1922. He served in the Dáil and Seanad, and participated in other forms of public service for the rest of his life. He and DeValera were the founding members of Fianna Fáil. When he died in 1979, he was one of the three remaining members of the First Dáil. He is buried in the Republican plot in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin.

Philip Gallagher was a witness to momentous events in Irish history. He also had the opportunity to hear Kathleen Clarke speak in Dublin just after her release from prison and met the famous nationalist Irish journalist T.P. O’Connor. He returned to Albany in mid-1919, just before the War of Independence began. His months in Ireland at such a crucial time in the making of modern Ireland lingered with him for the rest of his life.