Mary Rohan O’Callaghan

Rick Corrigan with his mother, left, Joan O’Callaghan Corrigan and his grandmother, Mary Rohan O’Callaghan.

On a snowy January afternoon, Mary Rohan O’Callaghan sat in front of a pot of tea with her daughter and son-in-law, Joan and Leo Corrigan, and grandson, Rick. She mused about the foolishness of the Irish who put their trust in the British.

Mary was born in Tralee, County Kerry in 1924, the oldest of the three children of Margaret Delaney and Patrick Rohan. She grew up in Tralee, married her childhood sweetheart, Richie O’Callaghan, and quickly had two children, Joan and Noel. During the recession of the 1950s, Mary and Richie decided to immigrate to the United States, and in 1957, joined Mary’s brothers in Albany. Richie O’Callaghan found work at Schaefer Brewery and later at Tobin Packing. Mary and Richie became involved in the AOH in the old building on Quail St, and their grandson, Rick, has carried on both the Hibernian tradition in the new building on Ontario St. and the telling of family stories to his own children.

Mary’s mother, Margaret Delaney, was born in 1891 in Roscrea, County Tipperary, and much to her parents’ dismay ran away to Tralee when she was 16 years old to marry John Lawlor. The couple had three sons in as many years and then John died suddenly in 1922 of the flu during the epidemic of the early Twentieth Century. Margaret, as a young widow with three children, went to work in a Tralee slaughter house to support the family. In 1923, she married a Tralee widower, Patrick Rohan, who had two sons. Patrick was a WW1 vet suffering from both a bad heart and PTSD, and the British offered no disability compensation. Margaret and Patrick had three children of their own, on top of Margaret’s three and Patrick’s two. Patrick’s disability left him unable to do steady work, but as an educated man in an age when literacy was not the norm, he earned a small income filling out government forms for neighbors in Tralee. Margaret continued to work at the slaughter house well into her 50s. She died at age 89 in 1980.

Mary reflects that her mother had a hard life. Not only was money scarce, but Tralee was rife with political violence. The southwest of Ireland, especially Tralee, was heavily Republican in the decades before the War of Independence, certainly during the war, and afterwards during the Civil War. Mary remembers her mother telling her about the Black and Tans. In July 1920 the Black and Tans arrived in Kerry to augment the RIC in defeating the IRA during the War of Independence, and began a campaign of terror in Tralee and the surrounding towns. Between November 2 and November 9, the Black and Tans, British army, and RIC launched an unprecedented rampage on the town of Tralee, today referred to as the Siege of Tralee: for seven days businesses were closed, a curfew was imposed, no food was allowed into the city, homes of suspected IRA sympathizers were burned, and people were shot for coming out of their homes after curfew. Reprisals for any IRA offenses continued throughout the month of November all over Kerry. Shortly after this, the Kerry IRA formed their fierce and relentless Flying Columns, known for guerilla warfare.

In Tralee, Mary’s parents were in the thick of it. Mary remembers her mother, Margaret, describing the night she carried a load of guns in her apron out to the nearby field. And she told Mary about the time the young mother across the street was nervous about her husband coming home after curfew. She opened the top half of the front door a crack to look for him, and was shot in the head by a Black and Tan sniper.

After the treaty and tragic Civil War, the IRA, as the anti-treaty forces continued to call themselves, was outlawed by the Free State government in 1928, but the organization remained alive, albeit less active, until its resurgence in the northern Troubles. Between 1920 and the 1970s, the IRA units existed primarily in the 26 counties carrying out occasional “border campaigns.” As in the earlier years of the century, the IRA in Kerry was more active than in other parts of Ireland. One Kerryman, in particular, Charley Kerins, is still well known in the town of Tralee and to the O’Callaghan family.

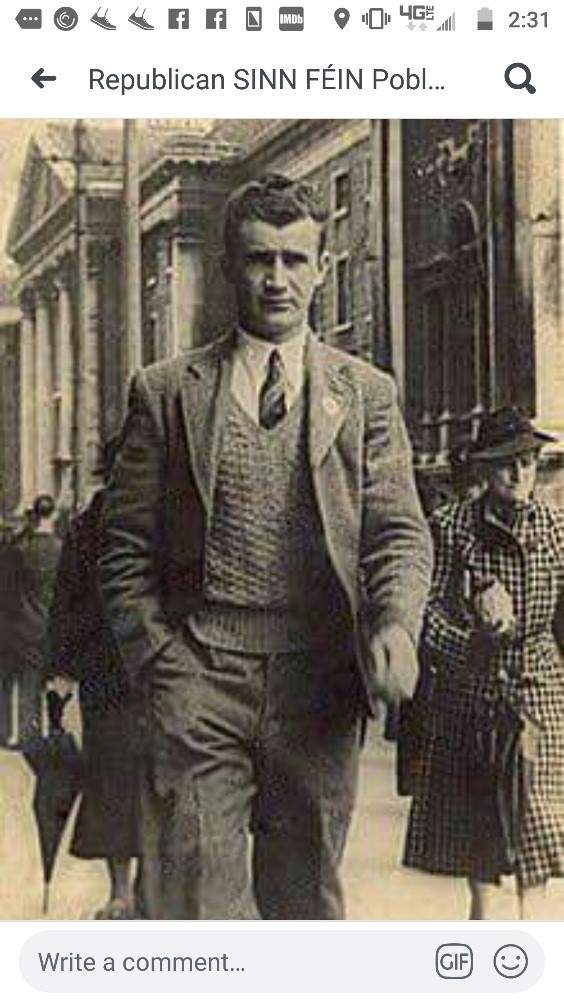

Charlie Kerins was born in Tralee in 1918. He won a scholarship to the Christian Brothers Secondary School and earned a seat at the National University of Ireland. He decided on a commercial course and began a radio career in Tralee. He was a talented football player, playing on the 1939 County Kerry All Ireland football team, and the Trelee football stadium today is named the Kerins O’Rahilly Stadium. In 1940, Charlie was sworn into the IRA. Because Ireland was determined to maintain its neutrality in WWII, the minor but frequent skirmishes at the border were particularly troublesome to the Free State. DeValera’s government recruited former Civil War republicans to head up a new Special Branch division of the police to infiltrate and squash the IRA. In turn, the IRA launched offenses against the Special Branch.

Charlie Kerins

On September 9, 1942, as Special Branch Detective Sergeant Denis O’Brien was leaving his County Dublin home, he was shot and killed. Witnesses saw three men in trench coats flee the scene on bicycles. A man hunt began using a list of IRA members. The top three members were from Kerry and the same three headed the wanted list, even though there was no evidence linking them to the time and the place of the shooting. One man, Mike Quille, of Listowel, was arrested in Belfast and quickly acquitted in early 1943 thanks to the solid representation by Sean McBride. Kerins was #2 on the list. After a wanted order was issued for his arrest, Kerins went on the run for 20 months staying in safe houses.

Many of the safe houses were in Tralee itself, and one was the home of the young Mary Rohan O’Callaghan. Mary remembers one night after she and her sister, Kitty, were asleep in their double bed, a breathless Charlie knocked on the door of the Rohan home. The family knew Charlie well; he had grown up in the same neighborhood. The guards were close on his heels, so Mary’s mother, Margaret, hurried him up the stairs and told him to get under the girls’ bed all the way to the wall. The guards were soon to follow. They came in and searched the Rohan home, including Mary and Kitty’s bedroom. The girls were terrified. After the guards left, Kitty told Mary that Charlie had asked for her hand to grab, so Kitty ran her hand down between the wall and the mattress and Charlie clutched it. Margaret hurried Charlie out the back door and told him how to get across the back fields without being seen.

Charlie was arrested on June 15, 1944, formally charged on October 2, 1944, and hanged on December 1 in Mountjoy Prison. He refused both representation and to say anything in his defense because he did not recognize the authority of the court. He was the last person executed by hanging in Ireland. Kerins was buried in the prison yard, but in September 1948, his remains were exhumed and released to his family. He is now buried in the Republican Plot at Rath Cemetery in Tralee.

Mary says everyone in Tralee knows Charlie was innocent and that he was the scapegoat for the DeValera government. There was no evidence linking Charlie to the crime, but the government needed someone to be made an example of. Some government officials and attorney Sean McBride loudly protested the validity of the trial, to no avail. The night before the hanging, all the people in Tralee came outside and said the rosary together. Mary’s son-in-law, Leo Corrigan, remembers that his father, who was on the Pro-Treaty side of the Civil War, came out with his comrades in their Free State uniforms for the rosary on that night. A monument to Charlie was erected in Tralee on Easter Sunday, 1947 in a park now named Kerins O Rahilly Park, and every year since 1947, a commemorative parade has taken place from the Pikeman Monument, commemorating the various risings against the British, to the Kerins Monument. Charlie’s memory lives on.

Author’s Note: Mary Rohan O’Callaghan delighted in telling the stories of her youth in Tralee, and I had a lovely afternoon with her in January 2019 taking notes for this article. I planned on visiting Mary on March 19 so she could read the first draft. On St. Patrick’s Day, 2019, however, Mary died surrounded by her family. Rest in Peace.